Not ready for a demo?

Join us for a live product tour - available every Thursday at 8am PT/11 am ET

Schedule a demo

.svg)

No, I will lose this chance & potential revenue

x

x

.png)

Here is a hard truth that usually takes about five years of production experience (or one day of deploying on a Friday) to accept: Your code is going to fail.

It doesn’t matter if you have 100% unit test coverage. It doesn’t matter if you used Rust (The massive CloudFlare outage is proof). It doesn’t matter if you performed a sacrifice to the Kubernetes gods. Eventually, a disk will fill up, a LLM will hallucinate, or an API you depend on will decide to return HTTP 200 OK with a body that says {"error": "lol nu uh"}.

Modern systems don't fail because developers are incompetent. They fail because our assumptions outlive reality.

The OWASP Top 10 2025 introduces A10: Mishandling Exceptional Conditions. It’s a formalized name for a pattern that has been burning down production environments for decades. Most security incidents today are not caused by clever exploits. They emerge when systems encounter states they were never designed to handle and react in unsafe ways.

This category is about what the system does when things stop behaving as expected.

Exceptional conditions are not rare events. They are normal events that violate mental models. In a local dev environment, latency is zero, the network is reliable, and the database never times out. You are God in that localhost:8080 universe.

But in production, your code is just a guest in a hostile house.

None of these are bugs on their own. They become vulnerabilities when the system treats them as impossible. If your system relies on an external factor to always play right, you are gambling on resilience.

Most systems are written as if execution were linear:

Real systems behave more like probabilistic graphs with failure edges everywhere.

Three shifts forced this issue.

First, distributed systems are now the default. Even small applications depend on dozens of remote services. Network unreliability is no longer an edge case; it is the operating environment.

Second, abstraction layers hide failure. SDKs retry automatically, SDKs swallow exceptions, and cloud services return partial success without telling you. Engineers mistake silence for correctness.

Third, LLM-driven systems introduced non-deterministic failure. A function can work syntactically while being semantically wrong. That breaks decades of defensive programming assumptions.

Security incidents increasingly originate from these blind spots. Attackers do not need memory corruption when they can trigger undefined behavior at scale.

Systems break. That is unavoidable. What matters is whether the system understands how it broke and how far the damage propagates.

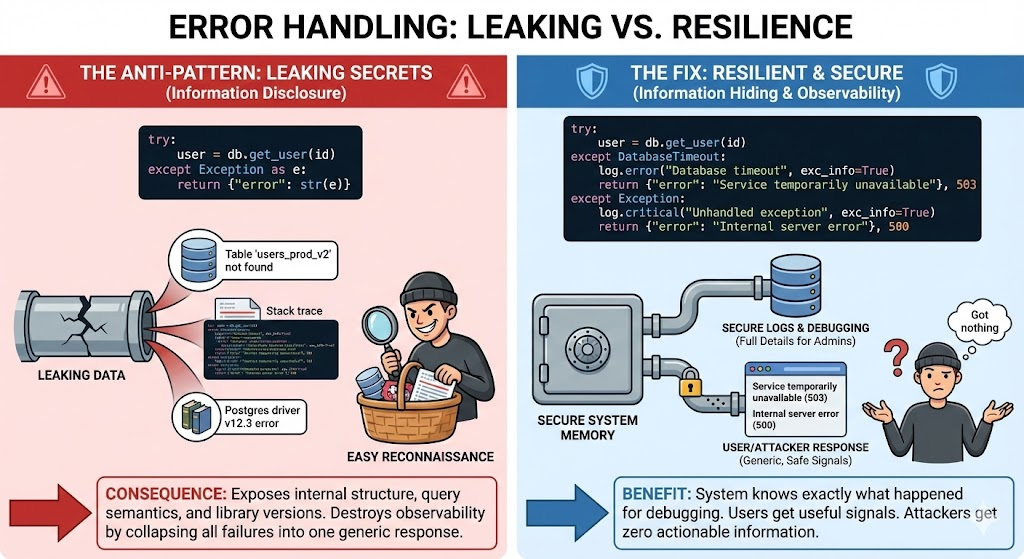

Consider a common anti-pattern:

try:

user = db.get_user(id)

except Exception as e:

return {"error": str(e)}

This leaks internal structure, exposes query semantics, and trains attackers about your internals. Worse, it collapses all failure modes into one response, destroying observability.

By returning str(e), you are leaking internal state. You might be exposing stack traces, database schema names (e.g., Table 'users_prod_v2' not found), or library versions.

Attackers love this. It saves them hours of reconnaissance. They don't need to guess if you're using Postgres or Mongo, your error message just told them.

The fix:

Resilience requires information hiding. The system needs to know exactly what happened, but the user and attackers should only know roughly what happened.

try:

user = db.get_user(id)

except DatabaseTimeout:

log.error("Database timeout", exc_info=True)

return {"error": "Service temporarily unavailable"}, 503

except Exception:

log.critical("Unhandled exception", exc_info=True)

return {"error": "Internal server error"}, 500

The system now has memory for debugging, users get signals, and attackers get nothing.

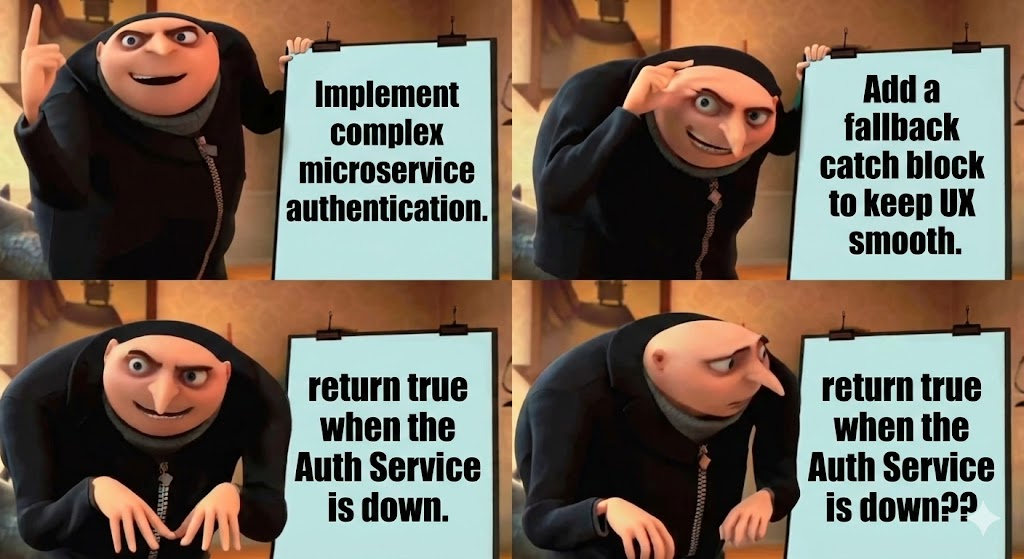

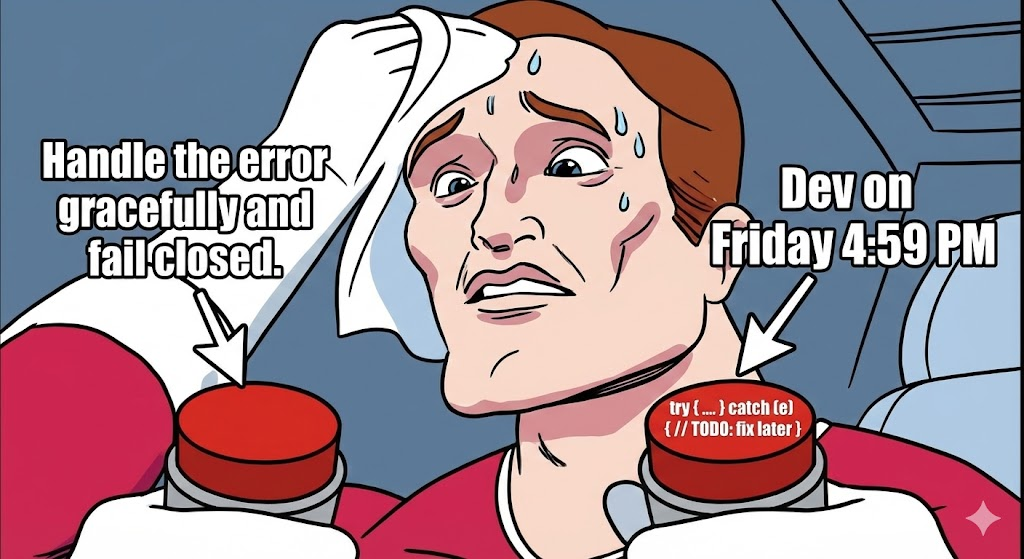

One of the most dangerous manifestations of A10 is accidental permissiveness. This often appears in authentication, authorization, or feature gating.

Engineers are often afraid of blocking legitimate users. So, when the authorization service is unreachable, they default to "allow."

// The "Let's be nice" pattern

async function checkAccess(user, resource) {

try {

const decision = await authService.verify(user.token, resource);

return decision.allow;

} catch (err) {

console.log("Auth service down, allowing fallback...");

return true; // <--- CATASTROPHIC FAILURE

}

}

This converts an availability problem like the Auth service being down into a critical security incident where everyone is Admin. A simple DDoS attack on your auth service now grants the attacker full access to your backend.

The Rule:

Correct behavior depends on context, but it must be deliberate. If authentication fails, the default should be denial unless there is a formally justified reason otherwise.

Security mechanisms must fail closed. If the lock is broken, the door stays shut. If you need high availability, you architect for redundancy, you don't bypass the lock.

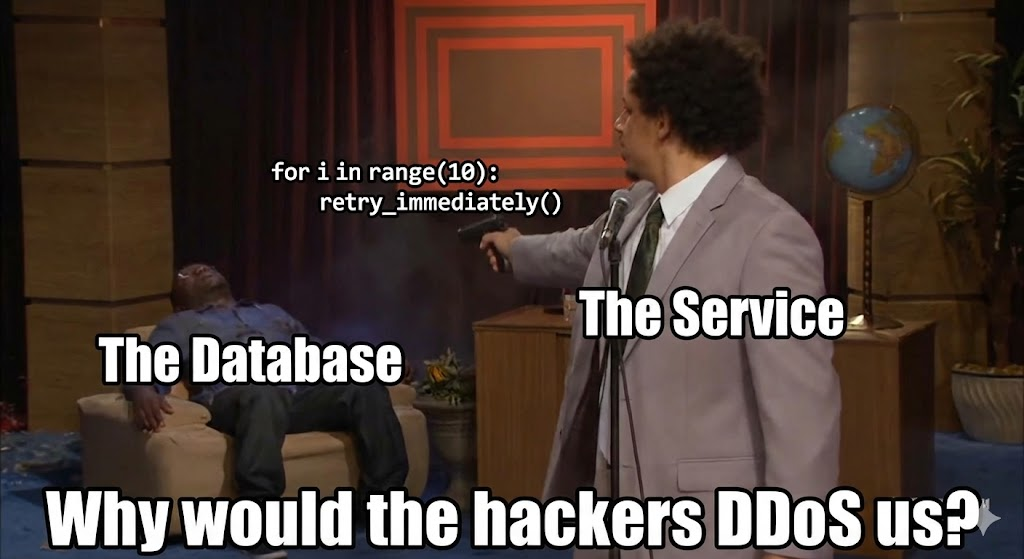

We are building distributed systems. Even simple apps now depend on three SaaS APIs and a cloud database.

When one of those services blips, naive code retries. When naive code retries in a tight loop, it creates a retry storm.

A naive loop multiplies load exactly when the system is least capable of handling it:

// The "DDoS Yourself" pattern

func callService() (*Response, error) {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

resp, err := upstream.Call()

if err == nil {

return resp, nil

}

// Immediate retry without backoff

}

return nil, fmt.Errorf("Service dead")

}

At scale, this behavior turns transient issues into outages. If 10,000 users hit your service, and your service hits the database 10 times per request instantly upon failure, you just hammered your struggling database with 100,000 requests per second. You have successfully DDOSed yourself.

Resilient systems introduce memory into failure handling using circuit breakers and backoff. You need to treat downstream services like they are unreliable by default.

The fix:

Implement a Circuit Breaker.

if breaker.IsOpen() {

return ErrServiceUnavailable

}

resp, err := callService()

if err != nil {

breaker.RecordFailure()

return err

}

breaker.RecordSuccess()

return resp

Circuit breakers convert unknown states into known ones. They limit blast radius and preserve system stability.

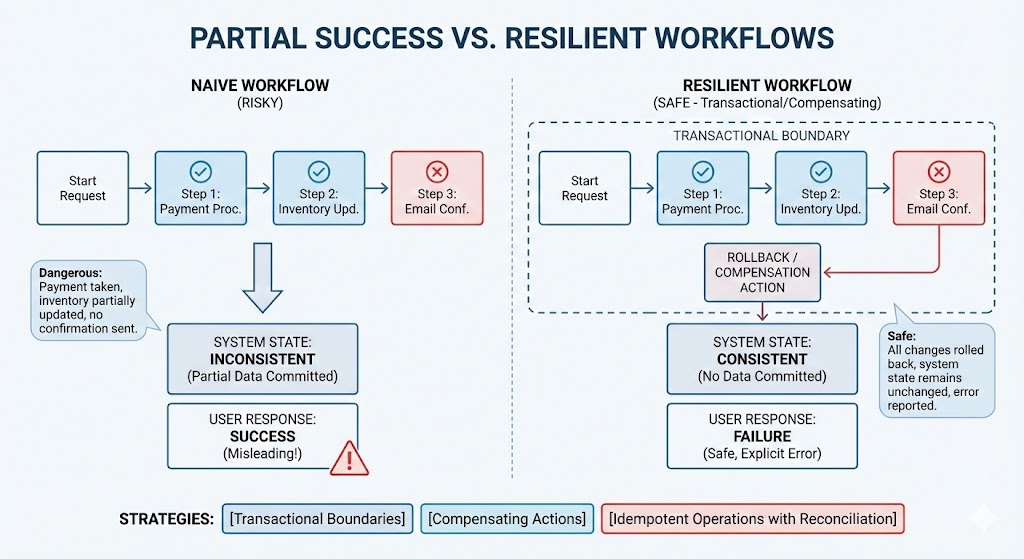

Another common failure mode is treating partial completion as success. In multi-step workflows, a mid-pipeline failure often leaves the system in an inconsistent state. The request returns success, but the data is corrupt or incomplete.

This is especially dangerous in payment flows, provisioning systems, and LLM pipelines.

The Fix:

Resilient designs enforce one of three strategies:

If rollback is impossible, the system must surface and track the inconsistency explicitly.

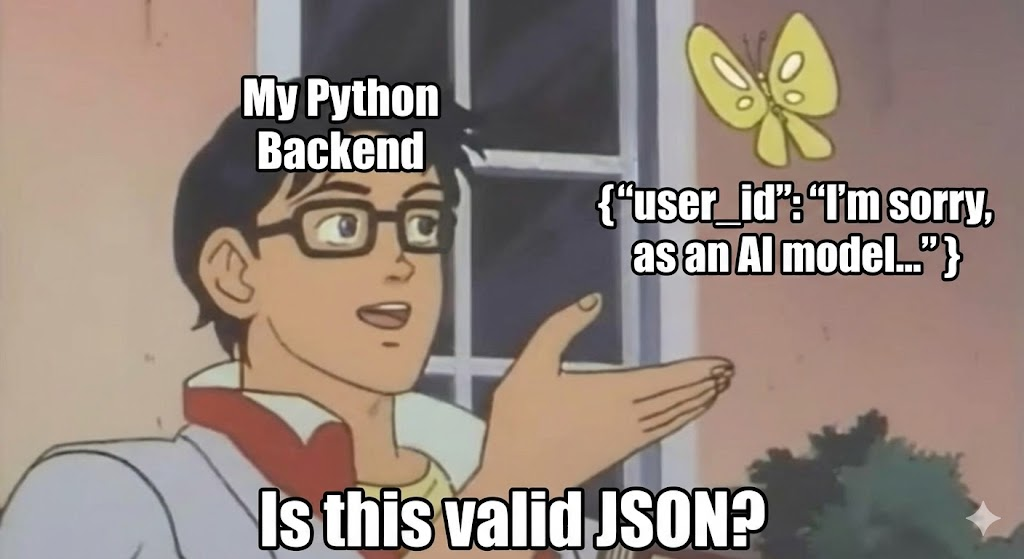

Here is where things get weird. With LLMs, we have introduced non-deterministic failure. LLMs introduce failure modes traditional systems are not built to detect.

A traditional function fails by throwing an error code. An LLM fails by confidently lying to you.

Consider a system that uses an LLM to parse user input into JSON for a database query. A dangerous assumption is treating LLM output as trustworthy by default:

response = llm.generate(f"Extract user info from: {user_input}")

data = json.loads(response)

db.insert(data)

If the LLM decides to be chatty ("Here is the data you asked for: {...}"), json.loads crashes. If the LLM hallucinates a field that doesn't exist, your database write fails.

The Fix:

Treat LLM output as hostile, untrusted input.

A safer approach treats the model as an untrusted parser:

result = llm(prompt)

try:

data = json.loads(result)

except JSONDecodeError:

log.warn("Invalid LLM output", output=result)

return safe_fallback()

LLM failures are rarely explicit. Defensive validation is mandatory.

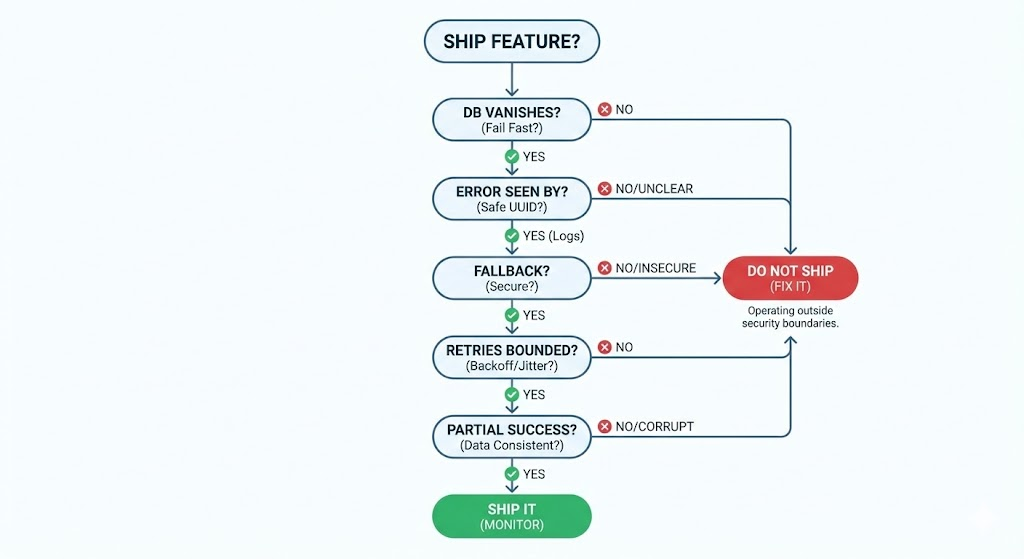

Before you ship that feature, ask yourself these questions. If you can't answer them, you aren't done.

If any answer is unclear, the system is already operating outside defined security boundaries.

Uptime is a vanity metric. True resilience is about maintaining control when the lights go out.

Any junior developer can write code that works when the network is perfect and the database is responding in sub-millisecond time. But secure systems are defined by how they behave when the world is burning down around them.

OWASP A10 is a reminder that attackers thrive in ambiguity. They don't need to burn a complex 0-day exploit if a simple unhandled exception forces your authentication logic to fail open. They are looking for the cracks in your logic, not just the bugs in your syntax.

You have two choices: wait for an adversary to test your failure modes in production, or break them yourself first.

Go get your hands dirty with the chaos engineering and threat modeling labs at AppSecEngineer. It is infinitely cheaper to crash a simulation than to explain a breach to your stakeholders.

Design for the crash. The happy path is a lie anyway.Secure systems aren’t built on happy paths.AppSecEngineer helps teams learn how applications actually fail—through hands-on labs, chaos-driven scenarios, and real-world security simulations.

OWASP A10: Mishandling Exceptional Conditions is a new category introduced in the OWASP Top 10 (2025). It formalizes the security risks that arise when a system encounters states it was not designed to handle (exceptional conditions) and reacts in an unsafe, ambiguous, or permissive way, leading to potential security incidents.

The addition of A10 was driven by three major shifts in modern software development: Distributed Systems as Default: Network unreliability is now the norm, requiring robust failure handling. Abstraction Hides Failure: SDKs and cloud services often mask true failures (e.g., automatic retries, swallowing exceptions), leading developers to mistake silence for correctness. LLM-Driven Systems: The introduction of non-deterministic failure (e.g., hallucination, malformed output) by Language Models breaks traditional defensive programming assumptions.

Systems breaking (failing) is unavoidable. Mishandling an exceptional condition occurs when the system fails but does not understand how it broke, or when it reacts in an insecure way. The core issue is ambiguity. For example, leaking a stack trace in a public error message is mishandling, while logging a detailed error internally and returning a generic, safe message to the user is proper handling.

"Failing Open" is an anti-pattern where a security-critical service (like authentication or authorization) defaults to allowing access when it encounters an error (e.g., if the auth service is down). This converts an availability problem into a critical security vulnerability, effectively granting unauthorized access.

The rule is that security mechanisms must fail closed. If the authorization service is unreachable or encounters an error, the default action should be denial of access, unless there is a formally justified and highly redundant system in place.

This happens through Retry Storms in distributed systems. When a downstream service (like a database) blips or slows down, naive code often retries the failed request immediately in a tight loop. If this happens across thousands of concurrent users, the system multiplies the load on the struggling service, turning a transient issue into a full-scale, self-inflicted denial-of-service attack.

A Circuit Breaker is a design pattern that adds memory to failure handling. It monitors calls to a downstream service: If errors exceed a threshold, it opens and immediately stops all further calls to the service, converting unknown states into known "Fail Fast" errors, limiting the blast radius. After a set time, it goes half-open, allowing a single test request through to see if the service has recovered.

Partial success occurs when a multi-step workflow fails mid-pipeline, but the system returns a success status. This leaves the overall system in an inconsistent state (e.g., payment processed but item not shipped, or data corrupt/incomplete). Total failure is explicit; partial success is silent corruption that requires complex reconciliation.

LLM output should be treated as hostile, untrusted input. Unlike traditional functions, LLMs can fail non-deterministically (e.g., hallucinate, return malformed JSON, or silently truncate). Defensive measures must include: Strict schema validation (e.g., Pydantic) before use. "Refusal" detection to catch instances where the model denies the request. Robust error handling (e.g., try/except) for parsing errors (like JSONDecodeError).

.png)

.png)

Koushik M.

"Exceptional Hands-On Security Learning Platform"

Varunsainadh K.

"Practical Security Training with Real-World Labs"

Gaël Z.

"A new generation platform showing both attacks and remediations"

Nanak S.

"Best resource to learn for appsec and product security"

.svg)

.svg)

.png)

.png)

Koushik M.

"Exceptional Hands-On Security Learning Platform"

Varunsainadh K.

"Practical Security Training with Real-World Labs"

Gaël Z.

"A new generation platform showing both attacks and remediations"

Nanak S.

"Best resource to learn for appsec and product security"

.svg)

.svg)

United States11166 Fairfax Boulevard, 500, Fairfax, VA 22030

APAC

68 Circular Road, #02-01, 049422, Singapore

For Support write to help@appsecengineer.com

.svg)